Troubadour Poetry Prize 2016

The following prizewinning poems were chosen by our 2016 judges Jane Yeh & Glyn Maxwell who read along with winning poets at our annual prize-giving event at the Troubadour on Monday 31st October 2016:

- First Prize, £5,000, Pasodoble With Lizards, Abigail Parry, London

- Second Prize, £1,000, Father, Dennis L.M. Lewis, Doha, Qatar

- Third Prize, £500, To the Headless Long-Stemmed Rose on a Staircase in the Subway, Kateri Lanthier, Toronto, Canada

plus (new!) Troubadour prizes (for London/South-East winners)

- £100 Troubadour restaurant gift voucher, Shogo Says, Kirsten Irving, London

- Bottle of Troubadour champagne, Monologues for Young Actresses, Barbara Barnes, London

plus 20 prizes of £25 each for:

- Patience, Andrea Holland, Norwich

- Threads, Audrey Ardern-Jones, Epsom, Surrey

- After all you discover it is about locks, Barbara Morton, Drumoig, Fife

- Balloons, Betty Thompson, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, Ireland

- Departure, Beverly Nadin, Sheffield

- Ode to an Octopus, Catherine Temma Davidson, London

- Writing Him Out, Elizabeth Parker, Bristol

- [La Madre wants not to be in the sea—], Geraldine Clarkson, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire

- Flight, Giles Goodland, London

- Fossils, Jennie Osborne, Ideford, Devon

- Vera, Keith Hutson, Wakefield, West Yorkshire

- Leeches, Lindsey Holland, Aughton, Lancashire

- by the aviary his brother sat down and wept, Mariel Alonzo, Davao, Philippines

- The Bird Woman of Nigeria, Noreen Ellis, Chicago, USA

- Advice for Girls, Phoebe Stuckes, Alcombe, Somerset

- Surfacing, Richard Aronowitz, Oxford

- Plague, Ruth Waterman, London

- Dieppe, Scott Elder, St Priest des Champs, France

Judges’ Reports

Jane Yeh writes…

I greatly enjoyed reading the wide array of poems that made up this year’s Troubadour International Poetry Prize. I was impressed by the variety and sophistication of many of the poems, as well as the range of subject matter, tone, form, and style. It’s a real pleasure to see the multiplicity of voices when you’re reading through hundreds of poems, by turns witty or haunting, meditative or urgent, tragicomic or deadpan. So thank you to everyone for entering. All of the judging was done on a completely anonymous basis — in fact, it took a couple days of spreadsheet checking, and no doubt double-checking, before Anne-Marie could tell us the names of the winners.

I was truly impressed by the quality, depth, and expertise of the winning and commended poems. The first-place winner, Pasodoble With Lizards, by Abigail Parry, was a clear standout with its linguistic energy, exuberant rhythm, surreal imagery, and intricate craftpersonship. I was dazzled by the poem’s momentum down the page and the artfulness with which words and phrases were repeated with variations; the strangeness of the narrative, the sheer imagination of the descriptions and metaphors and similes; and the sense of mystery, that no matter how many times you re-read the poem, you can’t be entirely sure you know what’s going on. I absolutely love this poem. Just stunning.

The second-prize winner, Father, by Dennis L.M. Lewis, is striking and compelling in a different way, with its own brand of momentum and narrative drive. The apparently simple, straightforward language and impassive voice allow us to follow along with the speaker’s experience all the more intensely, while there’s something hypnotic about the locations the speaker wanders through and the characters he meets. The more I read this poem, the more fascinated I was by its just-slightly-off reality, almost like a David Lynch film. I was also impressed by the writer’s restraint, the complete lack of sentimentality with which he writes about the search for father.

The third-prize winner, To the Headless Long-Stemmed Rose on a Staircase in the Subway, by Kateri Lanthier, was an especial favourite of mine. Its title is immediately intriguing and curious, and the rest of the poem certainly lives up to it. Every line is full of original, striking expressions to savour. I like the sense of rigour in couplets and end-stopped lines, as well as the subtle use of rhyme and the musicality of the language. The voice is fresh and appealing, while the submerged sense of loss is expertly suggested through images like cut sunflowers send up signal flares.

I also really admired many of the commended poems, including (in no particular order) Patience, by Andrea Holland. I thought this poem’s invented form, with its repeated phrases and circularity, was particularly effective, and the images were vividly physical.

I was also impressed by the form of Audrey Ardern-Jones’s poem Threads, which consists of one sentence extended over 16 lines, and which sensitively depicts a cancer sufferer’s life and death.

After all you discover it is about locks, by Barbara Morton, was an accomplished, dream-like prose poem that also looks wonderful on the page.

Departure, by Beverly Nadin, was full of precisely drawn details of landscape, a deceptively spare poem with a philosophical bent that lingers in the mind.

Catherine Temma Davidson’s poem Ode to an Octopus was an elegant, witty, well-crafted piece that does what it says on the tin, as well as being a loose sonnet.

Flight, by Giles Goodland, depicted a subtly touching story of parent-child relations, with a nicely understated, conversational style that draws the reader in.

I enjoyed the approach of Jennie Osborne’s poem Fossils, with its airy open-form layout that matched its delicate phrasing and imagery.

Vera, by Keith Hutson, was well crafted and evocative, a convincing snapshot of the past enlivened by a gentle, wry humour.

The Bird Woman of Nigeria, by Noreen Ellis, was a magically haunting poem whose criss-crossing repetitions had a sestina-like quality.

And last but not least, Richard Aronowitz’s poem Surfacing featured a compelling chain of images that told the story of a missing person with a skilfully suppressed sadness.

Glyn Maxwell writes…

What I savour most in a fine poem is that every line seems to dine on the one before, the same proteins seem to flower, the thing twists and repeats and alters and doesn’t, like DNA strands. In Abigail Parry’s Pasodoble With Lizards the word ‘two’ grows two more ‘two’s, ‘gilt mirror’ grows ‘gila monster’, ‘dumped’ begets ‘dozens’ begets ‘doubled’ and so on and on, and still the poem expands outward, the story tells itself – goes itself, since we’re talking about a Hopkinsy effect – well this is like that, and I like it immensely.

Do I wake or sleep in Father by Dennis L M Lewis? I don’t know, or mind, but it treats that dangerous chemical dream with rare responsibility – dreams are trivial in that they’re surreal but profound in that they’re universal, and here I feel the latter, the stumble through a scene both logical and crazy, fuelled by conscious need (‘the search for father’) and fooled by unconscious ones (‘soon I got waylaid’). A winning snap of an unwinnable game.

Kateri Lanthier’s fine poem To the Headless Long-Stemmed Rose on a Staircase in the Subway gets New York in all its grace and dirt, its capacity to slide you decades back or forth along a subway track or an avenue. The sad sigh of its quick wit – ‘You did yourself a party favour’ ‘Meanwhile, we’re gunning it’ – rides the poetic subway with the lyrical, ‘Peach-ache of ripeness’ and the wrung-out, ‘the sound of your plane leaving and leaving and leaving.’ The heart of civilization keeping its shit together in spite of everything.

Mariel Alonzo’s by the aviary his brother sat down and wept is elegiac and compelling, a study in perplexity and solitude – ‘why didn’t anyone’s throat soar?’ – as the speaker rustles in the embers of what time has taken back.

In Monologues For Young Actresses Barbara Barnes vividly and movingly captures the helpless transports of a schoolgirl as she first encounters literary beauty. Everything changes – ‘I am rehearsed/in weeping, I no longer cry…’ she mourns in her bliss.

Geraldine Clarkson’s amazing La Madre… that ‘wants not to be in the sea’ is most terribly alive and alone, its agony of restlessness the lament of any great soul marooned in the wrong world, smiling her ‘wide/smile of undoing…’

There’s a fierce fragility to Scott Elder’s Dieppe, from the sharp intake of breath that ends the first line ‘if’ – to identity itself slipping away, the woman still there ‘your own colour’ and yet gone ‘into that nightscape’…

‘Rivers/of need have gurgled here’ cries the speaker of Lindsey Holland’s Leeches, deep in a rich, troubled meditation in a chapel ‘soaked with passion’. Pinned to the pew, a despairing language broods and burns, the very agenbite of inwit.

Kirsten Irving’s Shogo Says, where three different lives of the nameless ‘father’ travel different roads to the same lonely place, is both funny and forlorn, details of lives exactly remembered but achingly transitory and suddenly not there.

There’s a brilliant, almost painful exactness to Elizabeth Parker’s Writing Him Out, where whatever needs to be written to the nameless him demands puncturing, squeezing, a bright scratch, a clot, a psychology crystallized in a single act.

In Advice for Girls Phoebe Stuckes elegantly skewers the inanities of digital life, where life is only aye or no, all things matter equally from murder to mascara, and if in doubt say ‘Beyonce’ till everything’s cool. Nailed it.

In Balloons Betty Thompson carefully, chillingly, recounts a loss-of-innocence story, delving deep into the stare of a child at a conjurer’s tricks, tracing its slow fracture into disquiet and dismay: I pressed till I found a bursting point…

Portia, Ruth Waterman’s witness to the coming of Plague, trembles with apprehension as she sees the sea…creeping in, do you notice?’ and sounds the first intuitive response to looming horror, as a poet in England should do, then and now.

2016 Winning poems…

First Prize

Pasodoble With Lizards

In every house, this room. The two of us,

the two of them, and two eyes looking, looking back

at two eyes looking – double locked. A hall of mirrors.

The frills go up. The zoetrope’s gone gaga. Lickety-split,

they’re off again – two whirring figures skipping house to house

and room to room, and sticking to the shadows. Off we go -

in the aesthetician’s house, the upstairs room. The gilt mirror

and its gila monsters, slumped and coiled and polished.

We watch them from the bed. Sweat fogs the glass. They move

whenever we do. In the hothouse, the reptile rooms. The tanks

are stuffed with bodies, lazy like dumped flex, dozens of them,

looped and doubled. Violet, scarlet, gold and black. Reflected back -

the clapped-out manor house, the red-red room. Fungus, brass,

red drapes, the full-length mirror. There they are again – two figures,

fugitives, gone with the snick of the aperture. But it’s all caught

on camera: how their shadows whisk their tails and dash for cover.

In the penthouse, the ballroom: two figures, wheeling, drunk,

that botched one-two. A cracked-up mirror, and two archaeopteryx,

confused and karking, snared. In the picturehouse, the panic room.

Someone fucked up: it’s all over. The couple clutch each other,

know they’re done for. Here they come, ATOMIC MONSTERS!

razing tower blocks and power lines, a clumsy little number.

What an awful bloody mess they’ve gone and made. You, boy,

in your hall of mirrors. And me – or my projection – gone

when someone flicks a switch. The two of us, the two of them,

caught up in our reflections. It’s all done with two-way glass,

with smoke and mirrors. Anyway, we made these horrors

and they follow us, they move whenever we do, keeping time.

I’m tired, love. This dance has skinned me down to nothing much.

Quick quick, we’ve got to hurry, set off running. Off we go —

our fingernails tick tick upon the road. And we could run forever,

but we’ll never shake them off, these hooligans, our lizard others.

They think they’re us. We don’t know any better.

Abigail Parry

Second Prize

Father

I’d come alone to carry on the search for father.

The institutional building where the search took place

was labyrinthine—there were many stairwells

and many doors to offices and apartments

in the stairwells. But this was where they’d told me

he would be. I entered a kind of vestibule area, where

many people crowded. At first, I seemed to know

where to look, but soon I got waylaid—at one point

in a restaurant-kitchen area, at another at a doctor’s

waiting room. An attractive, young bi-racial girl

passed by and told me that she too was looking

for her father. I followed her, but lost her amongst

another hubbub of people. I was still unhurried

and certain where I’d find my father. I imagined

him with a woman, charming her or already

engaged in sex. At this point, I asked a woman

in the corridor whether she’d seen a stocky,

muscular black man with a certain air about him,

and realised I was describing someone the woman—

a middle-aged black woman—would likely have found—

irresistible. It struck me I should have mentioned

his advanced age. Later, I was sure I saw him at

the top of a stairwell, talking with a woman. I was

certain now I’d reach him. I went up the stairwell

where I thought he’d be, but was confronted with

door after door, one looking like another. I listened

at a door where I thought I heard voices—a woman

with a whining voice that could have been my mother’s.

But the door was not an entrance—it was some sort

of exit or back entrance. I continued up the winding

staircase until I was out on the street, and looked upon

row after row of multi-coloured doors to different

offices, houses and apartments. I realised then that

it was hopeless. I’d have to go back to the beginning.

Dennis L.M. Lewis

Third Prize

To the Headless Long-Stemmed Rose on a Staircase in the Subway

The Master of the Large Foreheads is restless at the Frick.

In my beautiful lapis blue gown, I hailed a silkworm south on Fifth.

Orpheus, mute, on a gilt salt cellar. That’s his lot in life.

Each afternoon, from the subway singer: “Another day in hell…”

Not every sidewalk musician’s an undiscovered Joshua Bell.

But each one plays your heartstrings with a quaver of regret.

You did yourself a party favour and unzipped my dress.

A lab-made opal ring pulled the film over my eyes.

I intend to pit general knowledge against specific gravity.

Nature struggles to learn from itself. Meanwhile, we’re gunning it.

Peach-ache of ripeness: a beard in the throat. Pewter ware is “sadware.”

All I am is a pewter plate melted down for musket balls.

Planters crammed with chrysanthemums are the burial mounds of summer.

Even after death, cut sunflowers send up signal flares.

Nothing like the sound of your plane leaving and leaving and leaving.

Whenever I wish you Good Morning, it’s the living end of Good Night.

Kateri Lanthier

Shogo Says

(i)

My father was a doctor

Stinking always of spirits and swabs

and a thin film of permanent marker.

His hands the red of the ambulance cross

from feeling around in the warmth of other people

from irritant iodine, whipping up his eczema

from drink, quite possibly (most of them drank),

and he would bring me stickers of patched-up cats,

with a bright green ‘Brave Boy’ written beneath.

In fall we would sit in the garden together

and he’d say “Shogo”, so softly it made me look up.

Then he’d shake his head and listen to the leaves

and forget he’d said my name at all.

(ii)

My father was a chef

Stinking always of grease-coated washing water

And a sneezeful of S&B chilli powder,

his hands the red of beni shoga ginger

from pestling spices to please other people

from irritant vinegar, barking up his eczema

from drink, quite possibly (most of them drank).

And he would bring me leftovers too good for cats

with bright plum sauce drizzled top and beneath.

After closing, we would sit in the kitchen together

and he’d say “Shogo”, so sharply it made me look up.

Then he’d wipe down the counter and listen to the cars

and forget he’d said my name at all.

(iii)

My father was a fisherman

Stinking always of sardines and mackerel

and a nostril of harvested nori,

his hands the red of a lobster’s armour

from hauling in nets full of food for other people.

From irritant saltwater, getting in his eczema.

From drink, quite possibly (most of them drank).

And he would bring me tiddlers to feed to the cats

with bright silver bellies all wriggling beneath.

At night we would sit in the harbour together

and he’d say “Shogo”, so sadly it made me look up.

Then he’d close up his knife and listen to the waves

and forget he’d said my name at all.

Kirsten Irving

Monologues for Young Actresses

Foolscap taped to the gymnasium door signposts

‘Tempest Auditions’, lists names of maybe Mirandas,

fresh aspirants to the Community Players Theatre.

In the hushed line up we practice taming the racket

of our heartbeats with skilless breath control, over-glossed

lips intone mantra-like I do not know one of my sex,

no woman’s face remember etc etc directed feetwards,

like a diver’s prayer before falling. We cool clammy palms

against the breeze block wall, our usual wild prattle checked

by uncrushable ambition; we the teenage toothpicks primed

to prop open the eyes of this drowsy town, the latest wave

of grease paint junkies high on wallops of adrenaline, our

futures awesomely magnified projections on a flimsy scrim.

For weeks my audition piece has subtitled each day’s blah

routine, hence I cannot sleep nor eat as the words ribbon

across my mind screen. The bedroom glass has instructed

my hands in the manner of beseeching, my gaze schooled

in Elizabethan innocence. Trifling trills on my tongue-tip

like fizzy candy. Bashful cunning is a jewel I have turned over

and over in my palm for close examination. I am rehearsed

in weeping, I no longer cry. Sense memories are my stockpiled

ammunition. Prairie blizzards transcribed into catastrophe

at sea; January’s whiteout on the highway, a crazy chain

of mauled vehicles- God’s tantrum. And as for love, last

Wednesday’s spare between Algebra and English Lit; I rescued

the new boy’s pen before it skittered beneath the lockers,

where upon our eyes met and found that which they knew not

they had sought. I tell you I almost died.

The gym door consumes the girl ahead of me, I am next.

Out on Main, my dear father keeps the pickup idling

against the chill, tunes into ‘Sports Roundup’ to pass the time

till I return. His last minute advice, to just be myself.

Barbara Barnes

Patience

1.

of things to come, there is rinsing her face

with cold water cupped in each palm, but

a kind of refusing to gather, just a necessary

dousing the visible, mouth stuck in the shape

of prayer as water settles in the basin

and she rises to look at what wanting looks

like: It is undignified. It throbs in the bones

of the cheek, the full eye, giving up what’s

wished for. Unsteady mirror

ready the hands for the body, for the shape

2.

of things to come, out of your mouth

the other women call to me. You clear

your throat and drink from a glass

of patience. This is the marriage of tenderness

and kicks. You give me that look. I fall

into line, a thousand times wrong. I hear

the right words in the dark, feel the shape

of words shaken out of a song to sooth

the dying, drink in remembrance of me

the glass as a throat, in the shape

3.

of things to come, it will warm in his holding

as a good red. She gathers herself

in a ritual of belief, still awkward as hands

wrung in hope, ashamed to yearn,

they have earned their keep of his body.

The tongue holds more, understanding

persistence; the way a muscle holds on

to memory while the mind cleaves,

the body buckles. Be clean, be still

as water, mouth ready for its shape

Andrea Holland

Threads

She was twenty-eight when diagnosed,

black hair stolen by chemo, a blonde wig

with a fuzzy fringe; she told me she’d traced

her mother’s history to Kerry, gravestones

in churchyards; I listened to lives of forgotten

people, how mammy died when she was nine,

how granny and auntie were diagnosed

in their thirties; memories of offered masses

and sacred litanies; her hands in mine, arms

lighter than a doll, her face translucent

as almond soap; I gave a name for what she

already knew; spoke of fate as dice, told her

her siblings and children’s chances were as

birth, a boy or girl; her corn-blue eyes tracks

from both parents; after she died they came

for testing, fragments of light in the distance.

Audrey Ardern-Jones

After all you discover it is about locks

Barbara Morton

Balloons

A stream of them—long and ribboning before

they were inflated, breath-filled they turned into

globes and cylinders, fat demi-lunes ably shaped

by the long-fingered magician who, in his downtime

offstage from the Hippodrome, relaxing by the fire,

legs stretched across the hearth, would plunge

those long hands into his pockets, to pull out rubber

neon proto-chameleons. How he joined limbs and

torso, how he conjured heads, ears and tails, I never knew,

just watched this flow of colour and shape become

a rabbit or a cat. My own cat retreated to the yard

when this post-performance played out: a narrow

space, walled high with London bricks, it shielded her

but not me from the fear I felt when he threw his voice

out there to ricochet into the kitchen, a prelude

to his suite of tricks. There were cards among his props

that he showed and shuffled, got some gasps in return,

but not from me. As for the bouncy animal he gave me –

a red rabbit with swelling ears—I pressed till I found

a bursting point. This was after I had seen, through

the back window of his parked-up van, a cage of doves.

Betty Thompson

Departure

For days no wind

swayed

the single-minded rain

from the mountain side

and dark cloud

didn’t break; what fluke

weakens sky’s resolve,

sneaks

chinks of light through the canopy,

lets the relentless

tin roof racket

cease? Sudden hush

assails the ears

of stunned

shrieking macaques. Moon

squints through pines,

elucidates

a notion of mist,

picks out stalks,

dripping needles,

bracken tops, and we,

the berries and I, are shining.

At my back,

the wreckage

of the lodge;

a track leading down

is not the track I set out on.

Beverly Nadin

Ode to an Octopus

Dear beautiful sea creature, you glider,

eight-limbed mind, Kali-quick, boneless evader,

changeable as vapour, current in motion;

reading the world and matching it like paper.

Who could see you as nothing but belly, blinkered,

solving equations with your many-padded fingers?

You speak water in all possible directions, while

we hard-boned holders of gravity fall on our faces.

And what a mother, walled in with your brood,

your sacrificial body their red carpet to the future.

Who could eat you after hearing that story?

Not me, not ever, oh you curver around corners,

giver to move life onwards, not like us bumpers,

bulbous, stumbling, us generation-gulping gullets.

Catherine Temma Davidson

Writing Him Out

She punctured the cartridge

squeezed until dark blue words

slid into the slit of the nib.

When ink stopped she wrote a bright scratch

pressed the pen tip to her tongue

moistened a clot to free one more line.

She bled the nib in a glass

swilled out dark silt.

The plughole glugged up stained water

then swallowed him down for good.

Elizabeth Parker

[La Madre wants not to be in the sea—]

La Madre wants not to be in the sea—

its squallous aqua and uneasy upsidedownalia—

but to be the sea herself

now and for ever.

Is there anything like sea for being in? she asks the smoothed

rock, gilly with bladderwrack. H’m, precious?

to the backward-facing anemone, mouthing

praise to the oily rainbow.

She takes a big breath, opens the caverns

of her mouth, and seeks to ingest it all,

sucking up streamers of fish—

a weave of jellynose, soldier, dog, angel.

There’s a gigantic gobble and requisite

swallow— coral reefs and lost cities, whalebones

catching at the back of her throat—the smack of

salt, iron, iodine delight. Sweet stink and rampage

of heavy-bellied serpents—still-tongued

monsters—tangle-toed octopuses, wrecks.

Her skin gleams transparent, revealing

turquoise veins, bright bone creeks,

gorges, cut umbilicals, spirals

and spume… Her sides split in a wide

smile of undoing, a jumping

pulse. Her soul thrashes by.

Geraldine Clarkson

Flight

We are pulling our suitcases-on-wheels

through a large southern European city.

The cases rumble, and each time the pavement

changes, the noise changes. Somewhere here is

a station with a line to the airport.

Nina is telling me how late we are.

I do not tell her that she has not

factored in the extra time the shuttle-bus

will take, since this train, if we get to it,

will only take us as far as Terminal

One, when our impending flight is from Two.

It is hot, we have spent too long in the shade

eating ice cream, and she seems unusually

anxious at the end of our summer

time together about getting home. But

the thing is, even though I myself am

not worried, not too worried, however

hard she tugs at her suitcase behind her on

its tiny castors, she can’t match my speed.

At each street-corner I have time to look

at the map. She still has five years to grow.

I have maybe ten years before I concede

strength to age. For five years we may be matched

until I’m the one wheezing behind her

complaining about the heat, querulous

over the way home. But first I’m queuing

30,000 feet above France for the

toilet, and I feel suddenly as if we

could accelerate through time as one can

now through space and our stowed suitcases

were currently exploding into part-

icles, driving each one further from the

next, each incapacitating inch as

planetary, and my daughter tearing her

buckled self apart before me. I love

how I can catch her eyes but don’t. The queue,

suspended by the forced air, does not move.

Giles Goodland

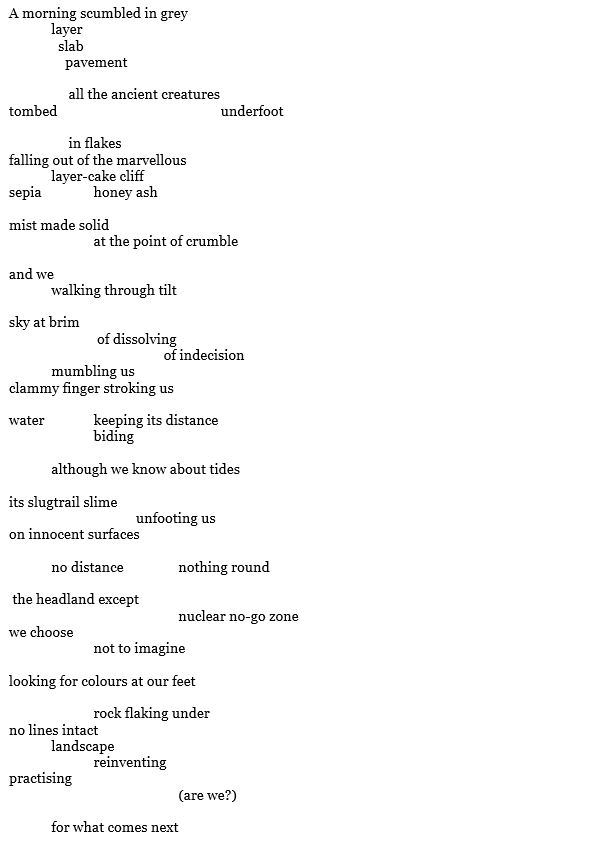

Fossils

Jennie Osborne

Vera

Even then it was a name for adults,

not an eight year old. In the backward stream,

worse at maths than me, she had no father

and a limp. Her mum was Mrs Worthington,

so we’d stand at her broken gate and sing

Don’t put your daughter on the stage, then run

until, one teatime, more worse for wear

than normal, Mrs W came round to shout

our antics at my dad. He listened –

placidly for him – before responding

Fair enough, but she’s hardly Tiny Tim.

I had a stab at fending off the strap with:

Vera doesn’t mind, she says she likes it.

Her mum’s drunk all the time and starves the dog.

If you don’t hit me I’ll apologize.

Before they took her into care, Vera performed

a vent act for the teacher with her Sindy doll

to Neil Sedaka’s Where The Music Takes Me,

ending on a happy happy happy happy day!

that left the class light-headed with respect

and must have taken years of practise.

Keith Hutson

Leeches

Verb: to leech, archaic, meaning

to cure, to heal. Alternatively

Noun: a leech, archaic, meaning

a physician, the leech

who leeches. Who among us

this Easter Sunday in Rosslyn Chapel

hasn’t hoped for a version

of leech? The blood of Christ

is sipped by the certain. I keep my hands

on my thighs and consider

the masonry: green men, knights,

a murderer peering

dumb from the nave. The whiskery man

beside me shakes my hand with a fervent

Peace be with you. I wonder what passes

palm to palm. Behind a stained glass

angel, the shadow of a pigeon looms

and a toddler wails I want. I want

to tumble from this talk of breaking

bread and bones, of triumph

in death. Archaic. To cover one’s flesh

with hypodermic creatures, expel

our dirt. Forgive us. We always lay

the blame elsewhere, do away

with instinct. Sinful, to be

this devilful of blood-filled skin,

to thirst for the redness I’ve seen

coursing through you, that I kiss.

To cure. To heal. There’s peace

in lip-to-lip, exchanging

perfect impurity. For centuries

this chapel’s soaked in passion,

the tongues of orators lubricated

by tomes and ancestors. Rivers

of need have gurgled here,

flummoxed by the business

of human life: unclean, unacceptable,

unloved by each other, unleechable,

damned in fact, never good enough

and not like us.

Lindsey Holland

by the aviary his brother sat down and wept

loose nerves of a cage he once touched

with hollow bones, where juvenile species

were incubated, shells unmapped. only

a single knot of light to soft-boil, keep

themselves from scrambling. they called

it sanctuary – a place where endangered

means fault-lined, folded into arks, entered

by pairs of animals, wish bones sparked.

where just before dawn, his brother would

count how many wingspans it would take

to reach the sun, praying his betrothed won’t

come with the slat of lumber, reteaching him

flight. his fingers reaching deeper into light

than ever when he was wild, when his mother

prophesied – son, you’re too much, why didn’t

he stop? overflowed? why didn’t she clamp

tore his beak, reclaimed each feather he owned?

why didn’t anyone’s throat soar? now, he kneels

before the sunken bed of his husbandry, ache

of ingrown claws heat-stroked from the last

snatched pocket, grafted marrow ready

to erupt – fuse and fuchsias. this nest he built

above arrest – ash fall, where ghosts perch.

Mariel Alonzo

The Bird Woman of Nigeria

In Lagos, a palm-swift fell from the sky, broke on the electric line, burned

and turned into an old woman, quickly surrounded by the angry crowd.

Witch, sorceress, the line of electric fire, flesh raised and broken, raw through

the ash blackness of her breasts. No longer bird, or human, just an old woman.

When she was younger, but still old, her lover’s hand, outstretched, spanned her

shoulders, fingers splayed searching for wings in the lines beneath her old bones

At her age she had learned to hide her birdness from the men she took as lovers

the terror of her beak, the rage of her song, the sharp sight of her black eyes.

When she was fledgling, the king stole her from her father, winning her with a ring

of gold and brass and silver, that flashed and blinded even the magpie’s eyes.

The wives of the king were jealous of her ring, of the flight hidden in the softness

of down. They were beautiful. They promised to save her if she taught them to fly.

She gave the king’s wives the bird secrets of balancing on small things, of far-seeing,

but not flight. The wives fed on envy and turned the king from his bird-witch wife.

The king sent her back to an empty roost, without the ring he used to snare her.

She took a line of lovers, learned to drink on the wing. Grew hard and old. She flew.

Most men never saw through her feathers, past the fullness of her bird breast

her rapid small heart, electric pulse, to the harsh line of truth stitched in hidden wings.

But the lover of her old age, had strong hands that held the all of her small back

the way a daughter holds a fathers’ will, casually, completely in the line of a palm.

He opened her again and she became witch and bird and girl. He wanted the all of her,

beak and rage and sharpest sight. She ate his eyes, rising into the sky and he saw

Her turn from bird to burned old woman on the ground, beaten and shot by the crowd

No longer bird, or human, just an old woman – a line, a ring, a bit of ash and feather.

Noreen Ellis

Advice For Girls

Vanilla based perfumes drive men wild

we have no evidence for this. Sudocrem

is good for spots, cuts, grazes, rashes

and sadness. Always accompany your friend

to the clinic. Boyfriends cannot be trusted

in this matter. Eyebrows are sisters not twins,

let this knowledge free you. Get a hot water bottle

for period pain, buy your own chocolate,

boyfriends cannot be trusted in this matter.

Nail varnish can be used to stop tights laddering,

if your tights ladder you cannot keep wearing them,

no it is not Punk. Get someone to help when dyeing

your hair, blot your lipstick. Don’t borrow mascara

from women you don’t trust. Text me when you get home,

keep your hand on the door in the back of the taxi.

I found his Facebook, I’m friends with his sister’s

best friend’s zumba instructor. Dairy makes you fat,

gluten is evil but we don’t know how or why or what it is.

Beyonce, Beyonce, Beyonce.

Phoebe Stuckes

Surfacing

The cracked Formica almost drove you mad,

the way it caught the sleeves of your pure new

lamb’s wool sweater. The film of dust

that coated every surface, every plane

of every object – “Too near the coal mine,”

you used to say – colonised your household

habitat the more you dusted it. The cake

of make-up that you lavished on your cheeks,

your eyes, your lips, was eaten by each day

and spat out on the pure new whiteness

of your pillowcases and your single sheets at night.

You always found the arrangement of the gravel

on the pathway up to your front gate somehow

asymmetrical. Your colleagues’ talk swam

on the surface of things, while you dreamt

of dipping below the noose of scum that chokes

the weir to see what lay beneath: it was that

or escaping to the Caribbean to learn to swim.

It has been three days now that the police

have searched your favourite stretch of river.

They have found nothing, which on the surface

is good: yet your passport is still lying

in your bedside drawer. I might have to wait

until the spring rains swell the river, the divers said.

Richard Aronowitz

Plague

I am Portia, daughter of the silversmith.

Here’s a stool – take it; we live in hard times.

What news on Cheapside? I hear a coffee-house

is coming, a new gathering place.

We shall talk.

The sea is creeping in, do you notice? The sea is bringing …

we shall not talk of that.

Yesterday I rounded a corner and came upon

a large plot of weeds and rubble; a starving cat

threaded through mounds of shapeless stones -

there will be a crumb of comfort for it somewhere.

A square of cotton sheeting hung on a dirty clothesline.

For months I’ve walked like driftwood through these streets.

You don’t know when …

One day I found a bridge I’d not observed before

and slowly climbed up to its mid-point,

to the top of its arch; I turned and waited.

The canal slept as tiny ripples fluttered.

The sun left the water first; then it left the rooftops.

Ruth Waterman

Dieppe

A quarter past two and you wondered if

your body were a breeze or a breath of moonlight,

if your children drew on the tide in the harbour,

or the dew-covered garden in their dream work.

They lay like feathers in a single bed. And you, at once

the lady in the window and the woman moving

down the cobblestone lane to a pier beyond

the bulwarks and pilings, blending, step upon step,

your own colour and form into that nightscape.

Scott Elder